Norse or Vikings myth is the corpus of North Germanic tribal myths. The Nordic myth dates back to Nordic paganism and extends through Scandinavia’s Christianization until the current Scandinavian heritage.

Likewise, Norse mythology, the northernmost offshoot of Germanic mythology, is based on Proto-Germanic folk tales.

Most comprise narratives of divine beings, creatures, and heroes extracted from several sources from before, during, and after the era of pagans.

Similarly, sources for most myths come from historical texts, archaeological characterizations, and folk rituals. In other words, Norse mythology alludes to the Scandinavian mythological fabric that existed during and after the Viking Age (c. 790- c. 1100 CE).

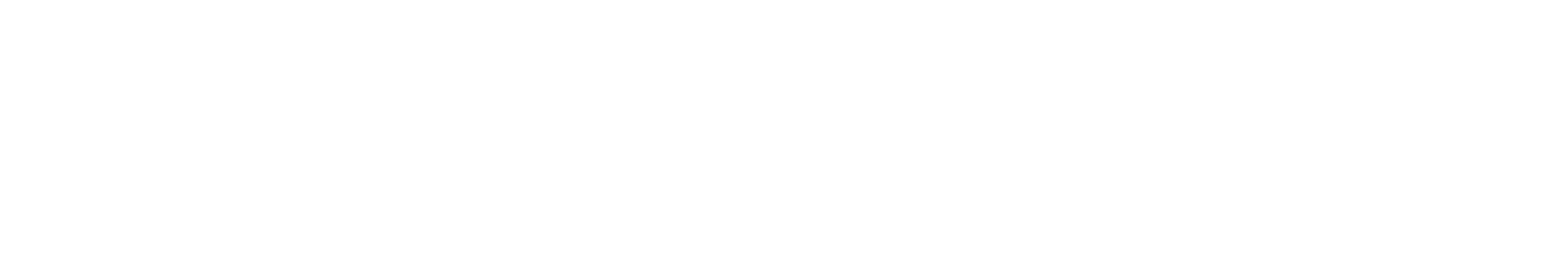

As such, the Nordic mythological realm is both intricate and extensive, with a story of creation in which the first gods murder a giant and transform his appendages into the world, many kingdoms stretched out underneath the World Tree Yggdrasil, and the inevitable annihilation of the known universe in Ragnarök.

Its polytheistic pantheon, led by the one-eyed Odin, has a plethora of diverse gods and goddesses revered through rites interwoven into the everyday lives of the traditional Scandinavians.

What are the Norse myths known as?

Content

Norse myths are also known as mythologies of Scandinavia. They originated from North Germanic peoples and date back to Norse paganism, extending through the Christianization of Scandinavia.

Is Norse mythology still alive and well?

Thor and Odin, the Norse gods, are still alive and well 1000 years after the Viking Age. Although people believe that the old Nordic religion completely vanished with the arrival of Christianity, there are still many people who practice worshiping old Norse deities today. In Denmark today, between 500 and 1000 people follow the traditional Nordic religion and worship its ancient gods.

Are there dragons among the Vikings?

Mythical dragons did exist in Nordic folktales. It’s no wonder that the Vikings carved dragon heads on the ends of their longships. However, they are vastly different from other dragon myths, like the tales of English knights. For example, the dragons mentioned in the Norse sagas are malevolent creations, like Nidhogg’s corpse. Nidhogg lives beneath the roots of Yggdrasil, the Tree of Life, and feeds on its roots.

The Primary Nordic Mythology Sources

Stripping back the textures of history to construct a truly comprehensive and accurate image of the myths, beliefs, and practices, as they were in the Viking Age, is no easy task.

It is even more difficult, notably for a predominantly oral culture like Scandinavia at the time. As a result, when it comes to the Norse gods, we only have the tip of the mythical fjord.

Norse mythology, majorly preserved in accents of Old Norse is a dialect spoken by the people of Scandinavia during the European Middle Ages and the predecessor of contemporary languages of the Scandinavians.

The preponderance of this Old Norse literature written in Iceland was the verbal heritage of the island’s pre-Christian population that was compiled and written down in scripts.

The process primarily transpired during the 13th century. Amongst many, the famous Prose Edda compiled by Snorri Sturluson and the Poetic Edda gathered anonymously are the famous ones.

In other words, we do have some genuine pre-Christian references that maintain components of Scandinavian mythology, most notably Eddic poetry, and skaldic poetry.

To elaborate, skaldic poetry was Viking Age, pre-Christian poetry primarily mentioned at courts by royals and their courtiers. This poetry is maintained in subsequent Icelandic manuscripts.

Similarly, the Poetic Edda’s Codex Regius also comprises an unidentified compilation of older Eddic poems, containing ten about gods and nineteen about heroes.

While some of these relate whole narratives, most of them presume – sadly for us – that their reader was acquainted with the mythological backdrop. Thus, these do not provide elaborative context to Nordic myths.

Moreover, artifacts from the archaeological record, such as amulets of Thor’s hammer Mjölnir discovered amid pagan tombs and miniature silver female figures regarded as valkyries or dsir (entities associated with war, fate, or ancestor cults) may also be perceived as images of Norse mythology.

Connections to other recorded strands of Germanic mythology (such as the Old High German Merseburg Invocations) may also provide insight through historical linguistics and correlative mythology.

Similarly, scholars’ broader parallels to the mythology of other Indo-European peoples have also led to the potential reconstruction of much older narratives.

Viking Society and Norse Mythology

The word síður, denoting ‘custom’ – the closest idea the Old Norse vocabulary had to religion – reveals the interwoven character of the Norse mythological structure in daily life.

Of course, it’s difficult to say exactly what the Vikings felt about all these distinct Norse gods and the environment they lived in.

However, archaeological evidence suggests that people had genuine allegiance to certain gods to whom they felt attached.

Ancient Scandinavians also associated customs and ceremonies as a regular part of daily life.

The sources also create the sense that the Norse gods had individual personalities rather than fixed territories. In a broader sense, gods were revered and invoked by the entire community.

For example, sites of putative cultic participation can be identified by the presence of a god’s name in place names, as in the case of Fröslunda (“the grove dedicated to the god Freyr”). The sources also indicate certain hotspots.

According to Adam of Bremen (who composed his narrative based on hearsay c. 1070 CE), there was a magnificent temple in Uppsala, Sweden, that contained figures of Thor, Odin, and Freyr, who were worshipped in times of hunger, illness, war, or when nuptials occurred.

As a result, there were numerous dimensions to Norse mythology’s role in Viking civilizations.

“Old Norse religion should not be considered as a static occurrence, but as a fluid religion that altered progressively through time and certainly had many local variations,” writes Anne-Sofie Gräslund, a professor of archeology at Uppsala University.

Ancient Scandinavia was a world full of faith in divine forces, each with its own set of attributes and purposes.

Nevertheless, the rising effect of Christianity on the Norse paradigm only progressively transformed by the second half of the 11th century CE.

Even so, because Vikings were polytheistic, they probably added Christ to their already extensive list of gods, and different practices and beliefs coexisted for quite some time.

Viking warriors also worshipped various gods amidst the Nordic pantheon, like Odin and Baldr. They were especially worshipped during times of war or adversity.

In fact, upon the Vikings arrived in Scotland, they introduced their own religion and beliefs into the existing European diaspora.

A good example of such is the tale of Rurik- the former ruler of Kievan Rus. A Varangian chieftain, Rurik arrived in the Ladoga region (modern-day Russia) in 862.

He built the Holmgard settlement, and also established the first dynasty prominent in Russian history, called the Rurik Dynasty.

Famous Female Vikings

In Viking culture, female warriors were allocated just as much as the male.

But because the bulk of the most renowned Vikings mentioned in Norse mythology is men, most people are unaware of the existence of female Vikings.

According to some studies, some of the most magnificent Vikings of all time were ladies, and they, too, struck dread into the hearts of everyone who saw them, men and women equally.

Listed below are some of the prominent female Viking warriors of all time.

Lagertha

We know about a legendary female Viking named Lagertha or Ladgerda because of Saxo Grammaticus’ Gesta Danorum.

This magnificent woman was part of a bigger group of female warriors who volunteered to assist famed hero Ragnar Lothbrok in avenging the death of his grandfather.

She charged into battle and massacred a slew of foes, ending in triumph. Lothbrok fell in love with her because of her extraordinary abilities and unwavering bravery, and he chose to make her his new wife.

Lagertha, being the mighty warrior that she was, declined this offer and instead attempted to keep Lothbrok at bay by erecting a bear and a dog in front of her house.

Unfortunately, this defense did not work because she eventually married Lothbrok.

Freydis Eiríksdóttir

Freydis Eirksdóttir appears in various historical accounts and is hence regarded as the most famous female Viking warrior.

Unlike shieldmaidens and Lagertha, Eirksdóttir assumed the position of a female Viking warrior without the assistance of her male counterparts. In actuality, Eirksdóttir was supposed to fight alongside other male Viking warriors.

Still, once the Viking expedition arrived on the shores of Vinland (now known as the Eastern coast of North America), they swiftly retreated from the enraged inhabitants.

However, this did not sit well with Eirksdóttir. Legend has it that she took a weapon from one of her slain companions, ripped open her top, and challenged the irate natives to a duel.

The natives were utterly taken aback, if not horrified, by this daring tactic, and Eirksdóttir was declared victors.

Hervor

Hervor is the heroine of Heireks’ Hervarar saga from the 13th century CE. It is also her granddaughter’s name, the daughter of her son Heidrek.

Hervor’s father, Angantyr, possessed a magical sword known as Tyrfing, but his opponent killed him in a duel, and the weapon was buried with him.

Hervor and her crew proceed to the Kattegat region’s island of Sams, where Angantyr is buried, summoning his soul, demanding the sword.

Her father’s spirit begs her to quit her mission, but she refuses. Finally, he opens his grave and hands over the magical blade to her.

The sword only causes difficulties for its owner, and Hervor has several excursions before settling down and marrying. Heidrek, her son, gets the blade, which causes him just as many difficulties as it did his mother.

After his death, the sword is passed down to his daughter, also named Hervor, who is killed in combat.

Hervor’s rejection of tradition and reluctance to back down at her father’s tomb until she receives what she came for is the most striking aspect of the narrative.

Nordic Mythology of the Gods (Æsir and Vanir)

In Norse religion, the Æsir are the gods of the main pantheon. Odin, Frigg, Hör, Thor, and Baldr are among them. Likewise, the Vanir are the second Norse pantheon.

The two pantheons fight each other in Norse mythology, eventually ending in a single pantheon. Unlike the Old English term god (and the Old Norse word goð), Æsir was never adopted by the Christian church.

The interplay between the Æsir and the Vanir has sparked a great deal of scholarly debate and conjecture.

While other civilizations had “older” and “younger” deity families, such as the Titans opposing the Olympians of ancient Greece, the Æsir, and Vanir are shown in myth as contemporaries.

The two clans of gods fought battles, formed treaties, traded captives, and intermarried.

In Norse mythology, the names of the first three Æsir- Vili, Vé, and Odin, all allude to spiritual or mental states (vili to conscious will or desire, vé to the sacred or numinous, and óðr to the manic or euphoric).

Likewise, as mentioned, the Vanir are the second clan of gods recorded in Norse mythology.

The deity Njörðr and his offspring, Freyr and Freyja, are the most renowned Vanir gods who join the Æsir as hostages following a war between the Æsir and the Vanir.

Additionally, the Vanir seemed to have been primarily associated with agriculture and fertility, whilst the Æsir appear to have been associated with power and battle.

However, in the Eddas, the word Æsir refers to male gods in general, whereas Asynjur refers to goddesses in general.

Freyr, for example, was referred to as a “Prince of the Æsir” in the poem Skrnismál.

In the Prose Edda, Njörðr is presented as “the third among the Æsir,” while Freya is consistently ranked second only to Frigg among the Asynjur.

Many of the Æsir’s antecedents are unknown in extant tales.

There are just three sons of Búri in the ostensibly ancient stories: Odin and his brothers Vili and Vé. The sons of Odin by giantesses are listed as Æsir.

Likewise, the relationship between Heimdallr and Ullr and the Æsir is not made explicit. Loki, on the other hand, is a jötunn (presumably Odin’s cousin and foster brother).

The Primary Male Gods of Nordic Pantheon

The tribulations of the deities alongwith the interactions with different other entities, companions, mates, enemies, or household members of those deities, are essential to tales of Norse mythology.

The primary texts indicate a plethora of gods. Given below are some of the primary male gods of the Nordic pantheon.

Thor

The most prominent god for the people of Scandinavia throughout the Viking Age, as proven by archives of personal names and place names, was Thor entitled the thunder god.

In mythology, Thor destroys several jötnar, the enemies of the heavens or humanity, and he is married to the elegant, golden-haired deity Sif.

Odin

In the extant literature, Odin is also constantly referenced. He is depicted as a god armed with a spear having only one eye and travelling the planets in search of wisdom.

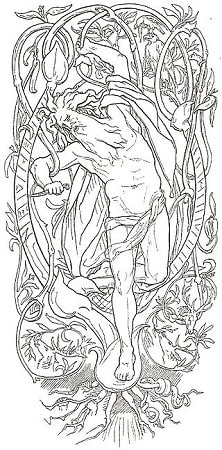

Furthermore, Odin is said to have strung himself in an upside-down position for over 9 days and nights on the cosmic tree Yggdrasil to learn the runic script, which he then bestowed as proper humanity.

He is strongly connected with mortality, intelligence, and poetry. In like manner, Odin is also shown as the king of Aesir and Asgard.

Loki

Loki was a crafty trickster in Norse mythology who could change his shape and sex. Despite his father being the enormous Fárbauti, he was counted among the Aesir.

Loki was portrayed as Odin and Thor’s companion, assisting them with their brilliant plots but occasionally causing humiliation and difficulties for them and himself.

He also appears as the gods’ adversary, barging into their banquet uninvited and demanding their wine. He was the primary cause of Baldr’s death.

Baldr

Odin’s bride is the formidable goddess Frigg, able to forsee the future, and together bear a loving son, Baldr.

In Nordic myth, Baldr’s demise is staged by Loki. This event follows a sequence of nightmares that Baldr sees coming.

After his demise, he dwells in Hel, a domain governed by the goddess Hel, daughter of Loki.

Bragi

In Norse mythology, Bragi is the god of eloquence and poetry and the patron of skalds (poets).

He is thought to be Odin and Frigga’s son. Runes were etched on his tongue, and he inspired humankind to write poetry by allowing them to drink poetry mead.

Bragi is wedded to the goddess of endless youth, Idun. Oaths were given over the Bragarfull (“Cup of Bragi”), and drinks were sipped from it in memory of a fallen monarch.

A king drank from such a cup before ascending to the throne. Bragi did not originally belong to the pantheon of gods.

Bragi Boddason was a 9th-century Icelandic poet. Later poets elevated him to the status of a god.

The Primary Female Goddesses of the Nordic Pantheon

Much like the Roman and the Greek pantheon, Nordic deities comprised a myriad of female goddesses.

Their veneration ranged from fertility, war, love, and sexuality to the weather, agriculture, and seasons, among many others.

Given below are some primary female goddesses of the Nordic Pantheon-

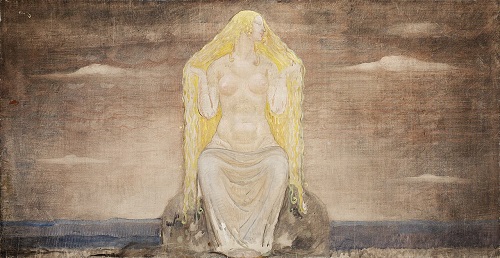

Freyja

Freyja is the Norse goddess of war, love, and death. She is the most well-known Norse goddess. Amidst the Nordic pantheon, Odin and Freyja must share the portion equally.

Her father was a sea deity, and her twin brother was Freyr, the god of rain, sun, and peace. When Freyja isn’t riding a boar with gold bristles, she’s flying in a chariot drawn by cats.

Freyja is often depicted wearing a feathery robe and performing seiðr. She marches to battle to consider which fallen soldier to choose amongst all and takes her choice to Fólkvangr, her eternal field.

When Odin was hanging from the tree of life, Freyja grieved and searched for her husband, who went missing for sometime, in distant regions.

Frigg

Frigg was the Norse goddess of foresight and maternity. Frigg’s Day – Friday is named after her. Moreover, Frigg’s magic allowed her to control fate and make events happen.

She is also frequently represented with a spinning wheel and spindle.

These artifacts represent the weaving of time. Frigg and Freya’s names were also somewhat interchangeable by the late Viking age, at least in written stories. Their characteristics were highly similar as well.

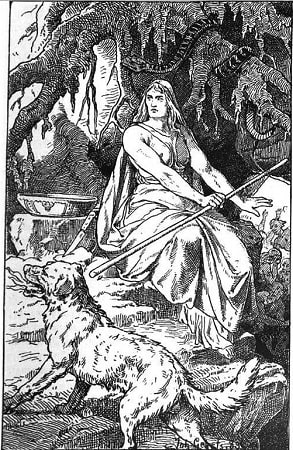

Skadi

Skadi is the Norse deity of winter, mountains, and hunting. She is a giantess typically depicted as hunting on skis in the high Alps.

Similarly, her name most likely originates from the word Scandinavia, which translates as “land of the Nordic countries.” However, nobody truly knows for sure which term originated first.

Her depictions include her hunting with a bow in the high mountains, which are perpetually shrouded in ice and snow.

She was formerly married to Freyja’s father, Njord, the god of the sea. But the two couldn’t agree on a place to live. Skadi did not adhere to the light, loud noise, and the heat of the sea.

She is unique among the giants for her kind disposition. She is favored in stories and was adored by the Norse people as a symbol of survival through cold winters.

Sif

Sif is the Norse goddess of the ground, houses, and crops. She is Thor’s wife, and her golden hair represents the wheat fields she works to cultivate.

She is an essential character in the Norse myth The Creation of Thor’s Hammer. Loki, the mischievous god, is claimed to have cut off Sif’s beautiful, golden hair one day.

Thor, the god of thunder, was enraged and prepared to punish Loki.

However, Loki persuaded Thor to spare his life on the condition that he find even better hair for Sif. As with many of the Norse goddesses, nothing is known about Sif’s life and legends.

However, we do know that in Old Norse, a variety of common moss is known as ‘Sif’s hair.’

Hel

Hel is the Norse underworld goddess. She is the offspring of Loki, and her name means ‘hidden’ in Old Norse. She keeps an eye on the dead that arrives in the underworld, known as Niflheim.

Hel is portrayed in Old Norse folklore as being half flesh and half blue, with a harsh and melancholy demeanor. She appears in a number of texts of Norse myths dating back to the 13th century.

Her name has such strong associations with death that it is now against the law in Iceland to name your kid Hel as of 2017.

Cosmology and the Tree of Life in Nordic Mythology

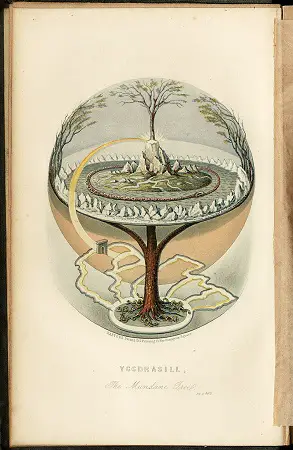

All entities in Norse cosmology live in the Nine Worlds, which revolve around the cosmic tree Yggdrasil. The deities live in the lofty kingdom of Asgard, while humanity lives in Midgard, a place in the heart of the universe.

Apart from the deities, the nine world, consists of humans, elves, dwarfs, and the jötnar.

The myths includes the description of the gods and entities travelling between these realms while interacting with humanity.

Likewise, Yggdrasil is home to a plethora of species which insults the messenger (squirrel Ratatoskr) and perches hawk Verfölnir.

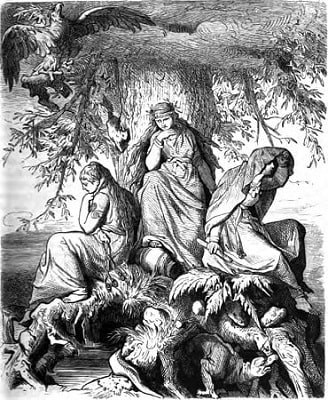

The tree contains three large roots, one being the home to the female creatures who are the members of trio of Norns and are associated with power of fate.

Elements of the cosmos like the Moon, Sun, Earth, and temporal units, like day and night are personified.

Similarly, in Norse mythology, the life after death is considered a complicated subject.

The deceased can travel to the dark land of Hel that is under the control of the deity of the same name. Or they can be transported faraway by valkyries to the great hall Valhalla of Odin.

Furthermore, they can also be selected by Freyja to live in Fólkvangr. The ones who die at sea is claimed by the goddess Rán likewise the dead virgins are taken by the goddess Gefjon.

Reincarnation is also mentioned in the texts. Time is given in two formats: linear or cyclic, while a few academics believe the cyclic time as the primary and the original format for mythology.

The Nordic Myth of Creation

Much like the myriad of folktales worldwide that depict the birth of our world, Nordic tales also have their own version of how the cosmos was created.

In Norse mythology, before the birth of time and the creation of the universe, there was only a great dark wide emptiness called Ginnungagap. This resulted in the creation of two realms: Niflheim and Muspelheim.

Niflheim formed in the north, and it became so dark and frigid that there was nothing but ice, frost, and fog.

The realm of Muspelheim formed to the south of Ginnungagap.

This became the country of fire, and it got so hot that it could only comprise fire, lava, and smoke. Surtr, the fire giant, lives here, among other fire demons and fire giants.

All the frigid rivers are reported to originate from the spring known as Hvergelmir. The name of these chilly rivers is Élivágar, which means “ice waves.”

Each of these eleven rivers has a namesake, but they are referred to as Élivágar as a whole.

Likewise, the water from Élivágar drifted down the mountains to the Ginnungagap plains, where it hardened to frost and ice, forming an extremely dense covering that grew in size in all directions.

Lava and sparks poured into the huge vacuum Ginnungagap from Muspelheim in the south.

The air from Niflheim and Muspelheim collided in the midst of Ginnungagap, the fire thawed the ice and it began to ooze, and some of the ice began to take the form of a humanoid figure.

This jötunn, often known as a giant, was Ymir, the first gigantic in Norse mythology.

When Ymir went asleep, he began to sweat, and the sweat under his arms developed two new giants, one male and one female.

One of his legs also merged with the other to form a third, Thrudgelmir “Strength Yeller.” These were the first of the frost giants, also known as jötnar.

The Birth of Odin and the Death of Ymir

Likewise, Audhumbla, the enormous cow, ate a slab of salty ice, and something weird transpired while she was eating it.

Some human hair sprouted from the block on the first day. Audhumbla nibbled on the salty ice block on the second day, and a head appeared.

Finally, on the third day, the rest of the body emerged. Buri, the earliest of the Gods, had emerged from the salty rock.

Buri was a colossus, tall and gorgeous. He and his wife Bestla would subsequently produce a kid named Borr. Borr and Bestla had three kids, Odin, Vili, and Ve.

Odin and his two brothers were worried by the fact that the giants dominated the Aesir, and that the giants were continuously giving birth to new giants. The only alternative they could think of was to kill Ymir.

So the three brothers prepared until he was asleep before attacking him.

A horrible fight ensued, and they succeeded to kill Ymir by using all of their might; the blood spewed out with a fierce force in every direction from Ymir’s body, and most of the giants perished in the massive river of blood.

The only ones to not perish were Bergelmir and his wife; the couple fled and found a safe haven in the country of mist, saving their life; all future giants are born from this couple.

The Creation of the Universe

In Norse mythology, the earth was created from the ashes of the gigantic Ymir. The three brothers brought Ymir’s lifeless body to the center of Ginnungagap, where they constructed the world from Ymir’s remains.

The oceans, rivers, and lakes were formed from the blood. The body was transformed into the land. The bones grew into mountains.

The teeth were transformed into rocks. The hair morphed into grass and trees. Midgard was formed by the eyelashes.

They hurled the brain up in the air, and it became clouds, and the skull became the sky, and Ymir’s skull became the lid that covered the new planet.

The brothers snatched some of the sparks emitted by Muspelheim, the region of fire. They propelled the sparks up toward the inside of the skull, where they sparkled at night and became known as the stars.

They constructed Asgard, the Gods’ dwelling, on the plains of Idavoll. The giants were allowed to settle in an area named Jotunheim, far away from Asgard.

Conclusion

The extensive publication of translations of Old Norse writings recounting the mythology of the North Germanic peoples extend references to Norse gods and heroes into European literary culture.

Nordic myths and folktales are particularly integrated into popular contemporary culture in Scandinavia, Germany, and Britain.

Moreover, references to Norse mythology became widespread in science fiction and fantasy literature, role-playing games, and, subsequently, other cultural goods such as comic books and animation.

Nordic religion can also be present in music, which has its own genre called Viking metal. As such, the prominence of Nordic myth is quite famous and still present to this day in various forms of art.